A Manifesto for Mental Health

Full Title: A Manifesto for Mental Health: Why We Need a Revolution in Mental Health Care

Author / Editor: Peter Kinderman

Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019

Review © Metapsychology Vol. 24, No. 49

Reviewer: Zsuzsanna Chappell

Skepticism about the current state of affairs in psychiatry is not new, as evidenced by a burgeoning literature that is likely to be familiar to the readers of this site. This book is an updated and extended version of the author’s A Prescription for Psychiatry (2014a). It is a valuable addition to the literature, as not only does Kinderman outline some of the problems in urgent and accessible language, but also offers thoughtful and seemingly workable suggestions for improving the care offered to those experiencing mental health problems. While it focuses on the situation in the UK, the arguments could be useful in other countries as well.

The book has fourteen chapters that can be divided into two parts. The first part covers the conceptual and theoretical problems surrounding contemporary approaches to mental health treatment. The second part is about practical improvements that could be made to transform the existing framework. Each chapter opens with a helpful summary abstract that signposts to readers what lays ahead.

Theory

The chapters in the first half of the book are written in a polemical, but readable style which means it is a book I could give to non-academically minded friends as well, something I always consider when reading books of this kind.

The introduction gives an emotional urgency the rest of the book. Chapter 2 lays the ground for the argument that difficult life events and our interpretations of them are key determinants for future mental health problems and chapter 3 details research that draws into question mainly biological explanations, whether genetic, chemical or neuroscientific.

These arguments re-iterate many of the main points of what is known as critical psychiatry. Writers in this tradition contest the notion that mental disorders are primarily brain-diseases. As Kinderman rightly points out, to say that something to do with the mind is somehow linked to the brain is a circular explanation. He argues for the key importance of social, environmental and biographic factors instead. He also argues against the use of the term “mental illness”, preferring the term “mental health problems” instead.

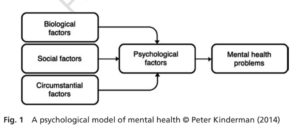

The positive arguments of the book really start at chapter 4. In this chapter Kinderman outlines the theory of mental health problems he has developed in earlier works. Accordingly, the first level of explanation is formed by the biological factors (e.g. low serotonin levels), social factors (e.g. poverty) and circumstantial factors (e.g. bereavement) of an individual’s life. These jointly cause the psychological disturbance which eventually leads to mental health problems. This is a readily understandable framework, but is not presented in great depth and any interested readers would have to turn to Kindermann’s earlier writings (Kinderman 2005, 2014b).

Chapters five to seven develop Kinderman’s argument that psychiatric diagnoses should be replaced with formulations instead. Psychiatric disorders, such as depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD or anxiety, have by now become familiar terms. Many people will assume that this is, if not the only way, but the best way to identify mental health difficulties. Kinderman argues that these terms work as limiting labels rather than a clear identification of a specific cluster of symptoms. The same disorder can present in very different ways in different people and psychiatry notoriously suffers from a problem of high rates of comorbidity.

Kinderman defines formulations as detailed, phenomenological, scientific descriptions of individual problems and difficulties. He argues that such descriptions are already readily available, together with corresponding numerical coding, in the ICD-10 and that they would be able to fulfill the same functions in service planning and offering treatment options as current diagnostic labels. They include not just personal experiences such as “depressed mood (MB24.5)”, but also personal circumstances, such as “low income (QD51)” or “history of spouse or partner violence (QE51.1).”

There are two main critiques of this approach. Firstly, such codified descriptions are not too far off from what the current codified diagnoses offer, and are reminiscent of the five axes introduced in the DSM-III, which have proven unworkable in practice (e.g. Bassett & Beiser 1991). Secondly, various “personal experiences of mental health problems” do co-occur, even if this may be for social and cultural reasons, rather than because mental disorders as laid down in current diagnostic manuals are natural kinds.

Practice

In the second part of the book Kinderman’s aim is to show how these principles could be put into practice. He is well placed to offer such practical advice, as apart from working as both an academic and a consultant psychologist, he has also served as president of the British Psychological Society and has extensive experience is advising on government mental health policy.

Chapter nine covers arguments against reliance on psychiatric medications. It is important to note that Kinderman does not deny that psychiatric medication can be useful for some people, but rather that it is only useful for a small minority and should ideally be taken over a short period. While available evidence (e.g. as cited in Rose 2019) appears to show that psychiatric medications are over-prescribed, I found the critique that these pills may help but do not cure less persuasive. Just as pain medication is part of the treatment for many conditions, as it helps to alleviate the pain without curing the underlying problem, psychiatric drugs can help to improve individual lives and be part of treating a variety of conditions. Thus they can be offered as a (possibly short-term) part of the longer term management of symptoms, rather than touted as a cure.

Chapter ten is about the need for provisions for those in acute crisis, usually in a hospital. Kinderman argues that the facilities currently offered are often dreary, overly security conscious and occasionally even unsafe. This can make people feel dangerous and undervalued. He calls for open and welcoming psychiatric hospitals that are more like four-star hotels, rather than hospitals. While this is a great idea in theory, it got me thinking about people who would feel less comfortable staying in a four-star hotel than a backpacker hostel when travelling. The emphasis might then be better placed on meaningful choice. More importantly, the author argues that such facilities should be perceived as safe and caring environments that minimise the need for compulsion and give people hope and optimism.

Chapter eleven is an all too short commentary on the mental health act, given the importance of legal coercion is mental health provisions. Kinderman is critical of community treatment orders and would like to see increased judicial oversight in cases of compulsory detention or medication.

Chapters twelve and thirteen offer an idea of the changes in working practices and organisation that Kinderman envisages. One facet I particularly liked was his emphasis on offering people support not just with their immediate mental health needs, but also with broader life difficulties. These could include debt counselling, family therapy, help with job applications or small business advice. In Kinderman’s vision, mental health care would be more closely aligned to social work and social services, and less intertwined with the medical system. He argues that psychologists could play a crucial role in pushing for change and need to be less acceptant of unjust practices.

Kinderman’s hope is that the changes he has laid out would add up to a Kuhnian paradigm shift in mental health provision. I am not convinced that this is the case, as I do not think that these changes are far reaching enough on their own. I believe that for such a paradigm shift to occur, the underlying theoretical framework that informs the psy professions needs to change, together with the cultural assumptions about mental health problems that predominate in society.

Works Cited

Bassett, A. S., & Beiser, M. (1991). DSM-III: Use of the Multiaxial Diagnostic System in Clinical Practice. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 36(4), 270–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674379103600406

Kinderman, P. (2005). A Psychological Model of Mental Disorder: Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 13(4), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/10673220500243349

Kinderman, P. (2014a). A Prescription for Psychiatry Why We Need a Whole New Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kinderman, P. (2014b). The new laws of psychology: Redefining “mental illness.” Robinson.

Rose, N. S. (2019). Our psychiatric future: The politics of mental health. Polity.

Zsuzsanna Chappell is an independent researcher writing on the ethics of mental health. https://zsuzsannachappell.com/

Categories: Philosophical

Keywords: Mental illness, health policy