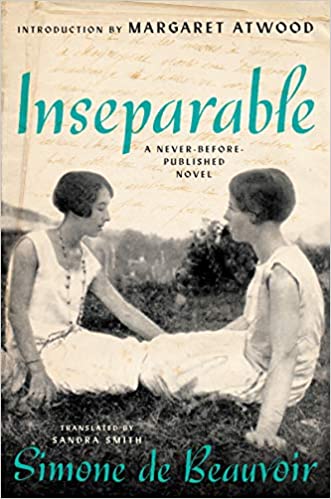

Inseparable

Full Title: Inseparable

Author / Editor: Simone de Beauvoir

Publisher: Ecco, 2021

Review © Metapsychology Vol. 25, No. 37

Reviewer: Finn Janning

Simone de Beauvoir’s novella Inseparable is remarkable in several ways: It was written in 1954 but has remained hidden away among her surviving papers until now. It is an autobiographical text from a prominent writer and philosopher. It is both a beautiful and a sad story about a friendship. It shows how rigid cultural norms and ideals can turn a life into a prison. It indirectly illustrates how one might liberate oneself through authentic love, friendship, and critical thinking.

Inseparable revolves around the meeting between two young girls, Silvie and Andrée, who meet as classmates in a private school in Paris during the First World War. We meet Andrée through the enamored gaze of Silvie, the narrator, who devoutly senses the details of the beloved, as here, where Andrée has hidden in the back garden to play the violin: “Her beautiful black hair was separated by a touching white side parting which one wanted to follow respectfully and tenderly with the finger.”

Later Silvie acknowledges, “Without Andrée my life is over,” and later, “I had a need to share all with her,” and still later, when Andrée tells about her first love with a boy called Bernard and claims that he was the only one who loved her as she was, Silvie says, “And me?”

Silvie is the smartest in her class; she is a free and critical thinker. For example, one day she is dazed by the obvious truth: “I didn’t believe in God.” Andrée is equally gifted—Silvie fears that she might be smarter—and appears through Silvie’s gaze and fascination to live in her own world. Andrée is more eccentric, unpredictable, and musical than Silvie but also deeply Catholic.

Silvie envies Andrée, especially her independence, until she learns that Andrée lives in a prison where her strict mother watches all the possible exits. Unlike her mother, Andrée believes in the idea of love-marriages. Her mother just wants to marry her daughters off without any concern for love.

Some might wonder whether the novella is about the friendship or love between the two young girls, later teenagers and young women. Making a distinction between love and friendship may be problematic, since true friendship consists of love—that is, trust, honesty, and equality. For example, Andrée challenges Silvie when she says that wanting to understand everything is haughtiness.

As mentioned, Inseparable is an autobiographical novella, Beauvoir scholars might debate how accurate Silvie is as an alter ego of Beauvoir—as well as Andrée, who was inspired by the author’s friend Zaza (Elizabeth Lacoin), who died in 1929, when she was only 21 years old.

Although I look forward to following the debate, the novella can easily stand alone as a sensuous story about friendship, love, freedom, and loss. Still, it may be tempting to tentatively place or interpret the novella through some of Beauvoir’s philosophical concepts.

In The Second Sex, Beauvoir writes that authentic love is “founded on mutual recognition of two liberties.” Authentic love is freely chosen or, to put it differently, without freedom, there is no love. Freedom is not only remaining loyal or true to your individuality (whatever that means); rather, freedom is becoming—that is, you are free to become whatever you choose, while you also make sure that the other is equally free.

The relationship between Silvie and Andrée is authentic. In contrast, an inauthentic love is one in which one party is hindered in experiencing freedom.

In Inseparable, it is primarily the strong Catholic upbringing and faith that guide Andrée’s family and hinder her free becoming. Her mother makes sure that she has so many tasks to do that Andrée intentionally cuts her foot with an ax just to get some free time. Inauthentic love is based on submission, control, and domination, whether by mothers and priests, as here; or gender, race, or religion in general, to name a few of the most dominant examples.

The novella might also open up the possibility that Silvie is dominated or restricted by her own ideals. For example, she believes that a woman cannot be free, creative, and innovative if she becomes a mother. Unlike her friend, Silvie doesn’t find the small twins (or babies in general) charming or attractive. Motherhood is apparently a hindrance to free thinking.

History has, luckily, shown that many women have become philosophers, writers, artists, and much more while being mothers.

The moral simmering in the novel is that there might not be only one way of being a mother but rather several. Motherhood is a multiplicity. At least, I cannot help but wonder what Andrée, who is capable of cutting her own leg with an ax, would do in a less self-harming way if a potential husband would hinder her playing her violin and writing her stories. Ideally, of course, she wouldn’t have to, if the marriage was one of authentic love. Continuing this line of thought, then no one would have to harm themselves, if they were brought up in a world of love—that is, one of equality and freedom for all.

Furthermore, since we are dealing with a novella inspired by true events, then Andrée was set to marry Pascal, who in real life represented Merleau-Ponty. Could they have matched Beauvoir and Sartre as not only the two dominating existentialists but also another example of aspiring philosophical friendship?

Returning to The Second Sex, then, one might also describe the relationship between Silvie and Andrée through Beauvoir’s use of the concepts “transcendence” and “immanence.” She writes: “Every subject posits itself as transcendence concretely, through projects; it accomplishes its freedom only by perpetual surpassing toward other freedoms; there is no justification for present existence than its expansion towards an indefinitely open future. Every time transcendence lapses into immanence, there is degradation of existence into ‘in-itself'”

Transcendence is a person’s ability to transcend a given situation, which, in theory, is possible for all human beings but in practice is reserved mainly for men—at least during the time where the novella takes place in France. For instance, Silvie transcends the Catholic faith. In contrast, a woman is traditionally held in immanence, where she is tied by her biological destiny: becoming a mother. A way to transcend this “destiny” is to throw alternative projects into the future. Silvie appears skeptical about whether a woman, whether Andrée can transcend her “immanent” destiny, but Andrée believes that another life is possible: another form of motherhood. Could Andrée (or Zaza) have found independence within dependence?

If you appreciate an intimate novella about friendship, freedom, and love, then read Inseparable. I truly enjoyed the book and recommend it warmly.

Finn Janning, PhD, writer and philosopher.

Keywords: fiction, literature