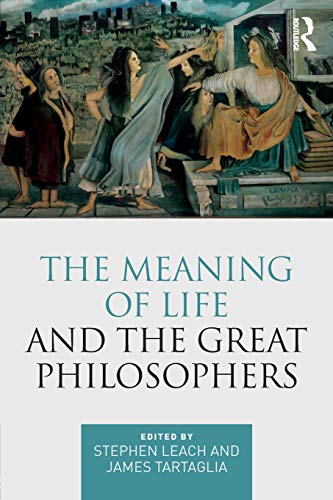

The Meaning of Life and the Great Philosophers

Full Title: The Meaning of Life and the Great Philosophers

Author / Editor: Stephen Leach & James Tartaglia (Editors)

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018

Review © Metapsychology Vol. 24, No. 23

Reviewer: Eri Mountbatten-O’Malley

Backgound

Alongside questions such as what is reality?… or what am I?, the question of the meaning of life (MoL) certainly seems to be one of the most fundamental philosophical questions of all time; a philosophical question par excellence. It is perhaps easy to forget however that the question is much more nuanced and modern then might at first appear. As many of the writers in this volume go to great lengths to outline, the problem of MoL really is really a western post-enlightenment, or more specifically, post-existentialist question. Great thinkers such as Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard (founders of what we might now term as existentialism) paved the way for a deeper analysis of the problem of the ‘meaning of life’ in the context of an increasing loss of faith in God and Christianity. Although the zeitgeist of logical positivism contributed to the diminution of these kinds of questions, preferring analyses of the meaning of words over ethics or religion, in recent years there has been somewhat of a blended approach to tackling questions over what we might mean by the meaning of life, or the meaning in life.

What this distinction helps to crystallise is that in conducting this kind of investigation, we are not doing so for some academic purpose alone, we are not, as Wittgenstein critiqued, ‘suffering from a loss of problems’. We are, rather, first and foremost interested in asking questions that fit a given problem or set of problems aimed at resolving (or contributing to resolving) those problems. This is a reflective process connected to both understanding and knowledge, as well as criteria and meaning for when we wish to explain a given phenomenon, we are precisely interested in understanding it better. As the editors rightly outline, ‘science cannot answer every question that interests us’ (preface, xi), thus, in order to avoid misdirected questions, what is vital is conceiving of a problem well from the outset. The way we ask such questions may lead the reader to concluding that the problem is either profound, or as some have suggested, incoherent. The key is to know how to ask the right question, and this is a difficulty that numerous contributors aim to tackle first. This approach works both as a strength and a weakness of the volume.

Structure

MoL is an edited collection which aims to bring together a range of perspectives exploring some of the greatest minds in the history of philosophy on the question of MoL. The topic is seeing some resurgence in philosophical interest and later in the summer there will be the Third International Conference on Philosophy and Meaning in Life (post Covid-19, this will now be delivered virtually) as well as the Meaning in life and the knowledge of death conference in Liverpool originally planned for July 2019 but now cancelled due to Covid-19.

Despite the fact that the editors lament not being able to include others, you would be hard pressed to imagine which philosophers in the history of ideas are missing here. The surprisingly comprehensive volume is structured around 35 chapters (plus a postscript entitled ‘Blue Flower’, which is a brief genealogical analysis of the concept). Each chapter is written by some of the most contemporary and influential thinkers of our time stemming from a range of philosophical traditions, including John Cottingham, Thaddeus Metz, A.C Grayling, Genevieve Lloyd and numerous others.

Each chapter then is a philosophical investigation by a modern philosopher on the philosophical ideas of other thinkers in history on the problem of the MoL. I use the term ‘thinkers’ here intentionally because some of the thinkers covered are by no means philosophers as we might traditionally conceive of the term. They are perhaps better described as religious or ethical leaders (though the distinction between philosophy and religion can be problematic). For example, the volume includes analyses of western and eastern thought including the musings of Buddha, Confusius and Vyasa, explored alongside Soctrates, Diogenes, Aristotle, Sartre, Rorty and others. As a result of the relatively recent historical development of the concept of MoL, each chapter aims to address the question of MoL either directly, or else inferred from within the broad corpus of a given thinker’s writings (or recorded sayings).

Does it work?

The overall aim of this volume is to produce an accessible volume on the MoL that is targeted at the general reader. It certainly achieves that. Each chapter is, as expected, authoritative, well-written and they largely tackle the challenge of dealing with such a complex topic rather well throughout; each contributor manages to write in a way that reflects their individual style with lucidity and succinctness. As suggested already, the notion of MoL is not always explicit in the works of thinkers from the past, certainly not in ancient text, so drawing the relevant themes from within those philosophical (or religious) texts is quite a feat.

For example, In the first chapter Kim and Searchris provide an analysis of the relation of MoL with Confusius. They discuss the tensions between personal and communal goods (deploring the former) and show how Confusian thought raises the prominence of family first and foremost, and relatedly, ritual and community. As Kim and Searchris suggest, it is only within the context of a ritual, community and family that we can create a space (a ‘healthy hive’) for meaning and human flourishing to even have a foothold. The personal good is made so through the acts of advancing the good of the communal. This relation between the meaning (of life, or in life) and human flourishing is explored throughout the volume by a number of other contributors too, each bringing their own analyses of the philosophical traditions which they build on to varying degrees of success.

I say this because it doesn’t always work. In some cases, it feels as though a contributor is mere following a pattern where they feel that they need to first shape their conception of MoL and then their focus. That might be fine for a stand-alone article, but when you read chapter after chapter in an edited volume it begins to feel a bit repetitive. In other cases, the connection with MoL, at least to me, seemed to be quite tenuous. For example, I found it very hard to read, let alone to see a connection with MoL in Chapter 16 (Montaigne) by Stephen Leach – though this may have more to do with my personal philosophical interests than anything else.

One chapter that stands out for me, however, was Chapter 34 (on Fanon) by Samuel Imbo. In that contribution Imbo explores Fanon’s political views and his drive for social justice. I am deeply interested in social justice, but for me the connections with MoL were too weak. If connections could be drawn through Fanon’s work then perhaps more could have been done to draw these out more perspicuously. Whilst political and social justice is absolutely essential in any society that wishes to provide frameworks for meaning and flourishing, it is no end in and of itself.

However, this is not always an issue in the volume and there are many examples where the risks of repetition is managed well, not least among some rising stars such as Reza Hosseini. In chapter 26 he successfully addresses the questions and problems of the MoL in the context of the opaque work of Wittgenstein by exploring Wittgenstein’s approach to philosophy through ‘aspect-seeing’, and the undogmatic life filled with ‘wonder’; his analyses are both subtle and insightful.

Overall, the volume is well structured, interesting, relevant and timely. However, my view is that more attention needs to be paid in the editing of the volume to ensure that contributors do not attempt to deal with the same issues repeatedly (or at least, if they do, to do so more discreetly). Nevertheless, definitely one for the bookshelf and certainly an enjoyable read. I look forward to reading some of the other edited volumes in the series from Routledge.

© Eri Mountbatten-O’Malley 2020

Eri Mountbatten-O’Malley: Eri is a Graduate Teaching Assistant at Edge Hill University. His interests are in human nature, concepts and normativity. He is an executive committee member of the British Postgraduate Philosophical Association (BPPA) and is in the final year of his PhD, a conceptual analysis of the concept of human flourishing.

Categories: Philosophical, Ethics

Keywords: philosophy, ethics, meaning of life